Vietnam is a land loaded with irony. You can buy hammer and sickle t-shirts, Che Guevara hats and Ho Chi Minh era propaganda posters just about anywhere. Breathtaking landscapes are occasionally obscured by smoke from burning garbage; shopkeepers smile and nod as they charge you triple the usual price; and authentic Vietnamese crafts, usually sold in roadside stands by petite elderly women, come from textile mills in China. It is a country where the American dollar is preferred over their own sovereign currency more than 40 years after the U.S. military left it in shambles.

This was our first visit to an actively governed communist country and our first experience in acquiring same-day visas. Despite America’s history with this region of the world, their government insists that all visitors pay for visas using American dollars – cash only. Border control and customs officers were all young adults wearing military-looking olive drab with bright red epaulets and braids, ribbons and shiny-starred hats that rarely fit. The guards wore no smiles, spoke no English and took their own sweet time in reviewing our passports.

THE FUTURE SHARES A HOME WITH THE PAST

Our driver collected us from the airport, loaded our bags into the back of a dirty Sprinter van and guided us into downtown Hanoi. Noi Bai International Airport itself is new and clean; its design is similar to a smaller Dulles and made for an easy welcome.

It is NOT an easy trip from Noi Bai into the capital city of Hanoi 30km away. For one, a two-lane paved road with narrow gravel shoulders is actually used as a four lane freeway in Vietnam. Traffic in the country is famous for its chaotic movement, and we experienced it first hand. It pulses more than it flows. Motorbikes move like starlings, swirling around large buses then slipping along the narrow shoulders. Intersections are a test of courage and size really does matter when it comes to owning the road. Mopeds lose out to cars, cars lose out to trucks, and all vehicles lose out to cars with government plates. The formula is really quite simple.

The first few kilometers were across the elevated highway on a levee-like rise above the rice fields and tiny villages scattered along the Red River Delta. The land there is flat, rimmed with big-leafed banana trees and viridescent quadrilaterals of sectioned rice fields in various stages of cultivation. The women tended the rice in traditional nón lá (bamboo hats), spreading fertilizer or shouldering equipment in massive baskets, sometimes while riding a bicycle. Family cemeteries, like defensive blockhouses, punctuated the landscape in elaborately carved gray granite edged with fancy ironwork.

The transition zone from the patchwork of farms into central Hanoi was abrupt. We entered one side of a giant traffic circle with an enormous hammer and sickle statue and exited amidst swarms of motorbikes carrying everything from newborns to air conditioners, live pigs to lumber. We were surrounded by locals wearing facemasks and fearless pedestrians crossing purposefully, threading gaps between hundreds of vehicles. Along the sidewalks, shop owners and their families sat on plastic stools smoking cigarettes and drinking beer. They sold phở (pronounced fuh), tailored dresses or motorbike parts, sometimes selling all from the same store.

Hanoi was unlike anywhere we’d ever been before. The average income there is a little over $2,000/year. And despite it being a city of more than eight million people, there were no visible highrises. No gleaming towers of commerce. Only narrow, four- to six-story ferroconcrete buildings in various states of completion or decay. Clothes hung out of nearly every window to dry in the cool moist air.

SAFETY BRIEFING

Our hotel was in Old Town, the most densely populated and chaotic part of the city. Tangles of power lines and cables hung thickly from posts and buildings, stretched in great bundles that looked like electric sinews. Dusk had settled into the air as we pulled up in front of the Calypso Grand Hotel – street lamps flickered on, illuminating the sidewalk in yellow. Once inside the lobby, Vivian greeted us with hot towels and fresh mango juice before providing an in-depth safety briefing. Mainly, she explained how not to get ripped off by street vendors, how to hold onto phones and cameras in public places and most importantly, how to cross the street.

For dinner, we walked a couple of blocks through rain and traffic to eat at the nearest phở restaurant. Four bowls of beef, four waters and one beer cost us around 200,000VD or about $10 U.S.

Our first full day in Hanoi was an extensive tour of the city with Luong, our local guide. He provided us with an exclusive look at its historic temples and monuments, and commentary regarding Hanoi’s position as the capital of Vietnam.

We walked through the beautiful and ancient Văn Miếu – Quốc Tử Giám, or Temple of Literature, and learned about the excruciating process applicants faced in earning the highest degrees at this imperial academy. It is dedicated to Confucius and its layout is similar to that of the temple at Qufu in Shandong, China – Confucius’ birthplace. Ranking and achievement governed which of the many doors and gates students could pass through during their studies there, and it limited how far into the temple complex they could enter.

THE BODY OF HO CHI MINH

Luong, like many of our guides throughout Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia, spoke English with a very heavy accent, making it difficult to understand precise suggestions and details. So, when he asked if we’d like to see Lăng Chủ tịch Hồ Chí Minh, which he translated into something that sounded to me like “Ho Chi Minh’s something-party-something,” I agreed. I thought the “something-party-something” was perhaps an HQ for the Communist Party. But it wasn’t. It was to see Ho Chi Minh’s body and mausoleum.

Ho Chi Minh was born Nguyen That Thanh in the province of Nghe An in central Vietnam. His father was a teacher and judge who advocated vocally for Vietnamese independence, to the point of losing his job with the imperial government. For 30 years, from 1911-1941, Thanh traveled the world and became influenced by rising communist political and economic ideas; he later founded the Viet Minh, a communist-dominated independence movement, ostensibly to fight the then occupying Japanese. It was at that time that Thanh adopted the nom de guerre Ho Chi Minh (Bringer of Light). Over the next several decades, Ho Chi Minh marshaled his countrymen toward the creation of a sovereign state, fighting against the French and the United States in the well-known wars.

On September 2, 1969, the anniversary of the founding of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam, Ho Chi Minh died from heart failure. And despite his wishes to be cremated, his body was embalmed and put on display. The mausoleum, which CNN International ranks as the “6th Most Ugly” building in the world, is located in the center of Ba Đình Square.

We waited in line for more than 45 minutes along with hundreds of Vietnamese retirees and students. The rules for queuing are strictly enforced. Women cannot show shoulders. Legs must be covered. No talking. Everyone must walk two-by-two. Hands cannot be in pockets and arms must not be crossed. Ronan was called out by a white-suited guard for a hand in his pocket, and Asher got cited for wearing his sunglasses in line. Other than those minor infractions, we cycled smoothly through the gray and red granite building and passed Ho Chi Minh’s body in absolute silence.

How did he look? Well, embalmed. Kind of like a wax replica. But overall, they did a great job for a guy who has been dead for 45 years. One person we met during our time in Vietnam suggested that the body was a fake, noting that it appears considerably taller than a man known for his small stature. But “Uncle Ho” is a highly regarded figure among Vietnamese people. He is featured on all their money and every community center, school, government building and park has his image prominently displayed.

DEAD-EYED STARES

The final bit of adventuring for the day was our cyclo tour from the Đền Ngọc Sơn, or Temple of the Jade Mountain, to our hotel. Cyclos are three-wheeled bicycle taxis where the passengers sit in front of the driver – or peddler, as the case may be. This was to be a forty minute ride through the very heart of the old town. Most of the ride was past buildings and temples we’d passed by already, and all the locals stared at us as we wheeled by. Parade of the tall white tourists.

THE ‘HALLELUJAH MOUNTAINS’ OF HẠ LONG BAY

We were picked up at the hotel early the next morning to be transported to Hạ Long Bay, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, famed for its thousands of limestone karsts and islands. Visually, they are reminiscent of the Hallelujah Mountains, the floating islands from the movie “Avatar.” On the way out, we got the ubiquitous “lunch break” stop during which the driver gets a free meal for dropping off tourists at a gigantic, warehouse-sized souvenir shop. We walked through it more as a courtesy to the driver than with any real intent to purchase.

Once we arrived at the port, our bags were sent off to the Prince III junk boat that would be our home for the next two nights. On board, we settled into our cabins and met our fellow travelers, a family from Australia with whom we would become good friends over the duration of our tour.

After four hours of sailing, we anchored in Bái Tử Long Bay, where Asher and I jumped into a kayak for a paddle among its caves and lagoons. Bái Tử Long was selected by our captain because it is much quieter than the heart of the Hạ Long Bay area, and indeed we passed only a few ships as we rowed through the glassy aquamarine waters. Asher immediately spotted several large jellyfish and touched the top of one of them (no stingers on the top). It was tawny-colored and the size of an exercise ball, and sadly hard to differentiate from the many plastic bottles and bags that also floated in the bay. Unfortunately, a lot of our kayaking excursion was spent netting out trash from this otherwise beautiful sea. Occasionally we saw oil slicks that spread across the surface like insidious rainbows, and avoided others that looked like raw sewage. Needless to say, we did not go for a swim.

Further irony, despite the modest portions that its slightly-built citizens enjoy throughout the nation, our cruise served us enormous quantities of steamed rice, fresh vegetables, beef, squid, pork and chicken. It was like a series of Thanksgiving feasts, and we quickly learned to take only a small amount from each course. They were also fancy – with carved radish roses and dragons shaped from carrots – and were clearly intended to be photographed before eaten.

THE FLOATING VILLAGE AND PEARL FARM

After a quick breakfast and short cruise to another lagoon, we boarded a motor boat over to the local villages of Cua Van and Vong Vieng – floating villages, where nearly 700 fishermen and their families live. They catch fish which is then sold in the markets on the mainland, and they grow oysters for their pearls. We sat in their school, a one-room classroom with dilapidated desks and an old chalkboard, while our guide Huong taught us a few important Vietnamese words. He emphasized the proper pronunciation of phở, which can be misinterpreted as their word for ‘streetwalker.’ Good lesson.

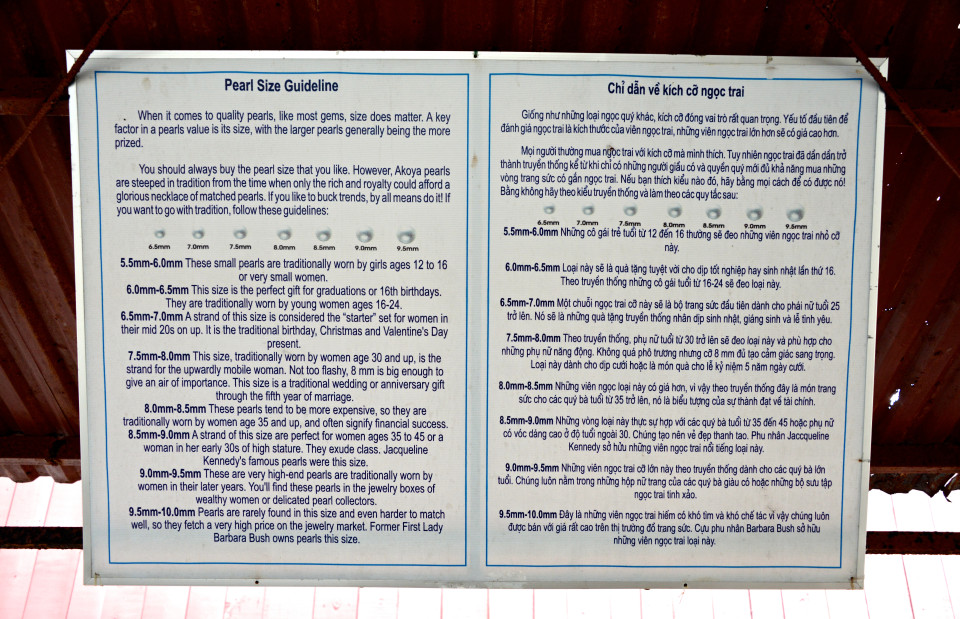

The village itself is a collection of wooden buildings atop Styrofoam or blue plastic barrels that form manmade islands nestled into the tiny coves of the bay. Residents are exceptionally poor, surviving mainly on tourism and fishing to provide an average annual income of around $1,000. The wealthier residents have tables and chairs and tiles roofs. At the end of the village tour, we were rowed over to the pearl farm and ushered through the jewelry store that contained nearly every color and size of pearl one can imagine. It also included a large chart recommending the kind of pearls appropriate for women based on their age, and featured a picture of Barbara Bush sporting the same type of the largest pearls they sold.

TROUBLE WITH THE AUTHORITIES

If you ask the boys what their favorite part of Vietnam was, they would say the BBQ on the beach. The crew of the ship navigated us over to a private island with a large cave and prepared an incredible feast of fresh fish, prawns, steak, fruits and vegetables that enthralled the boys. While we were enjoying our meal, the island’s two resident dogs barked at an approaching motorboat with two uniformed men standing in it. All of the crew, our guide and the island caretakers urgently began talking with one another while the first mate and captain came ashore from the junk. The approaching boat, said our guide, was the local government authorities arriving to confirm that our visit was approved. They also required some kind of ‘fee.’ To me, it looked like a shakedown, and our hosts said it was a common occurrence.

After a hike through the cave high on the island cliffs then a long kayak trip, we returned to the boat for our final night’s cruise. As we departed nearly three hours after they’d arrived, the government officials were still on the island reviewing paperwork and filling out forms.

FISHING FOR SQUID

Asher spoke no Vietnamese and the captain spoke no English, but the two of them bonded over squid fishing. A bright light was hung over the front starboard side of the boat and various fish, shrimp and squid surfaced beneath it. Armed with a large net, Asher would scoop up the catch and flip it into a large white pickle bucket. Over the course of an hour, the duo captured a half dozen squid. The small creatures inked as they sloshed about in the bucket, turning the clear water to an opaque blue.

SAYING GOODBYE TO FRIENDS

Hạ Long Bay is a very busy port in Vietnam and a key distribution point for huge quantities of coal and cement. After our final breakfast aboard the Prince, we entered the shipping lanes for our return to shore and threaded between massive cargo ships and multi-tug barges passing into or out of Hạ Long.

We’ve met a lot of fantastic people on our travels, but few compare to the family we met on the boat. Bill, Nadine, Roger and Sharyn, a family from Australia, were exceptionally warm, and in many ways felt like an extension of our own. We dined with them and kayaked with them, and Asher swam with them … a lot. They shared their wine with us and we all swapped stories about our respective travels. Once the boat landed and our bags were loaded, we reluctantly parted with our new friends.

Angela and I consider safety the #1 concern when we travel – avoiding certain areas, sticking together, securing personal items in our backpacks and coordinating reliable transportation. Locals in Vietnam will tell you that despite an occasional ‘grab and go’ theft of a camera or phone, it is a relatively crime-free place to visit. They say that the biggest safety risk to tourists is in crossing the street, riding a bicycle through traffic or driving.

So, with that in mind (and it was constantly on our mind), Angela was unhappy that our van for the four-hour trip back to Hanoi arrived with no seatbelts. None. After a good fifteen minutes of searching the floor and the driver telling us through a translator to ‘not worry, I will drive safe,’ we insisted that they find us another vehicle. Finding a van with seatbelts wasn’t a problem, but finding a van willing to drive all the way to Hanoi without a prior reservation was. Huong, our guide from the cruise, helped negotiate with the dispatch team. We had to wait an hour and deal with the emotions of an angry van driver who didn’t understand why we’d care so much about something so irrelevant as seatbelts.

WORLD’S GROSSEST SQUAT TOILETS

Sa Pa, a frontier town in the northwest part of Vietnam, was a five hour drive from Hanoi that we started early the next morning. We picked up another driver about 30 minutes into our journey; the two of them alternated navigational responsibilities. From our perspective, it seemed more intended to give the driver someone to talk to in Vietnamese. The drive itself was along a combination of major ‘interstate’ freeways and rural one-lane gravel roads, and took us from the low country into the arid mountains. Unlike the rice fields in the river valley surrounding Hanoi, these were sheer steps that serrated the mountain ridges.

The squat toilet is the predominant form of toilet in Asia. Unless you’re staying at a hotel or visiting a restaurant that attracts a fair number of Western foreigners, it is often the only option. In case you don’t know, the squat toilet is essentially an evacuation pan that sits at floor level, sometimes embedded in the concrete flooring. Finding clean toilets in Vietnam was tough, but finding clean squat toilets was impossible. One of the worst was at a half-built rest stop on the road south of Lào Cai, where the outdoor squat toilets sat surrounded by threadbare sheets flapping in the wind.

BAHN – OUR SHAMAN GUIDE

The Sa Pa district is one of the main trade villages in the mountains less than 15 miles from the Chinese border. Although considered ethnic minorities in Vietnam, the Hmong and Dzao people represent a majority in this region. Their customs give this area of nearly 40,000 a distinctive texture that is as colorful and dynamic as it is coarse.

While we were eating our lunch at the hotel, and Ronan was admiring the sizzling beef and rice on the next table, a diminutive woman with a giant smile (revealing a single gold tooth), came over to us. Hello, I’m Bahn, she said. I’m your guide. I’ll wait downstairs for you to finish lunch, then we go for our first walk okay? Unlike most of the guides so far in Vietnam, Bahn’s English was exceptional and had the hint of an Australian accent. Many of the Hmong guides in Sa Pa have learned English from tourists.

On the outskirts of town, between a motorcycle shop and a roadside shack selling waters and beers, we marched down a dirt track that fell off steeply from the narrow road. It was 90 degrees and humid and we were stiff from the long drive from Hanoi, but we quickly loosened up as we absorbed the primitive scene before us. Stepped rice terraces serrated the mountain ridges that sloped down to the river below. Children, covered in dirt and clothed in oversized t-shirts or traditional dress, played along the paths that criss-crossed the valley. We paused at the four-room school of kids aged 5-10 who sat hushed and stared at us as we peered through the open doors.

This was the Black Hmong village of Ma Tra, a place that only recently opened itself to tourists and still sees very few, and our starting point for three days of hiking and living among the hill tribes in Vietnam. It was also Bahn’s village.

As we neared Bahn’s house she invited us in to see where and how her family live. Her house was roughly 20’x12’ built atop a level concrete slab and sheltered from the elements by bamboo and a tile roof. In this respect, she appeared to be wealthy, as most of the houses in the region have dirt floors, discarded plywood siding and corrugated steel roofs. Inside the main living area was a small cardboard box with a 13” TV, blue plastic stools, a large wash basin and various nylon lines strung across for drying clothes. On the back wall she had a couple dozen pictures and postcards, yellowed on the edges and distorted by water. They are the only images Bahn ever sees of herself, as she has never owned a mirror. An open wood fire in an adjacent room is used for cooking and leaves the air smoky and the blackened rafters coated in soot. The kids, including Bahn’s three daughters and a couple of nieces she cares for, had their own sleeping area with thin mats on the floor. She was extremely proud of her home.

MAKING THE KIDS CRY

As we passed through the heart of Ma Tra and into the adjacent village of Ta Phin, children would start crying and hide when they saw me. Bahn explained, whether true or not, that unruly or stubborn kids are told that if they don’t behave, a big white man will come to the village and take them away. The children, and there were many in all the tribal villages we visited, smiled and approached Angela and the boys, but stayed as far away from me as possible.

Bahn is a shaman, a healing practitioner who supports the village and acts as an intermediary between spiritual and real worlds. I was chosen, she said, after a long illness of several days in fever. I saw things…visions…and became a shaman from then on.

MARCHING OVER THE MOUNTAINS

Early the next day, we headed into the heart of the ethnic villages surrounding Sa Pa, hiking through an elevation gain of around 1,500 feet over ten miles. There were other tourist hikes along the roads, but we saw very few outsiders throughout. We had chosen a route through the villages that would give us the most authentic and unexplored feel possible, so Bahn took us along ridges and through valleys that exposed the natural living conditions of the tribal peoples. We saw Black Hmong, White Hmong, Red Dzao, Tay and Xa Pho people, identifiable by the scarves and sashes they wore.

The hike was difficult and some stretches more dangerous than others – steep cliffs that fell off the side of mud-slick paths. It was also very warm with temperatures in the upper 90s and very humid. At an altitude of over 5,000ft, we were more frequently fatigued and stopped often to rest and rebuild oxygen levels. We passed through rice paddies being worked in preparation for the growing season, which meant that the farmers were burning off the weeds and rebuilding the irrigation walls. Along the trails we discovered sheltered plots where villagers cultivated green tea and cut through towering bamboo forests.

It’s worth mentioning that we saw far more women working the fields than men; it’s fairly common to see women working harder throughout many parts of Vietnam. By contrast, we encountered quite a few men drunk on rice wine either yelling at children or stumbling along. Bahn steered us clear of known alcoholics and shared with us their backstories.

After a long and sweaty day, we reached the home of Hen, our host for the homestay in which we’d eat, converse and sleep with a local family. There we met fellow guests Ron and Lisa from New York and enjoyed their company. When you’re on the road full-time and in a country where even basic communication is sometimes difficult, it is a treat to speak with fellow travelers from home. Hearing about their travels, rewarding work and two daughters helped make our homestay all the more enjoyable.

Hen prepared an incredible meal of rice, cabbage, beef and chicken; and of course, an ample supply of home brewed rice wine (a sweeter and milder version of sake). Neither Hen nor her husband spoke any English, but the atmosphere was convivial. Hen smiled as the boys wolfed down their beef and chicken. Their daughter of six sat in front of their TV watching Chinese kung fu shows.

LU – THE VILLAGE DRUNK

Near the end of the meal, a very inebriated stranger stumbled in and whispered to Hen’s husband, who then pulled up another stool for him to join our dinner. His name was Lu.

Lu was perhaps around 40, but it’s tough to tell with the tribal people who all look a lot younger than they are. Lu was absolutely filthy from his elbows to his hands and he filled the room with a wild smell more akin to a bear or raccoon. His smile was enormous and he laughed a little at us, as I’m sure he saw the alarm in our faces at his sudden appearance at our quiet family meal. Hen’s husband poured Lu a shot of rice wine from a plastic Aquafina bottle and the man immediately raised his glass.

In Vietnamese or Hmong or some combination of both (translated for us by Bahn), he shared a lengthy cheer to our health and safety and the abundance of the meal in front of us and a bunch of other things before proclaiming something that sounded like ‘Ju su quay it’ and then shot his rice wine. We of course did the same in observance of culture and not wanting to offend. Then Lu walked around the table and shook each of our hands. We all stood and accepted his hand graciously, nodded at him and smiled into his red watery eyes.

But he wasn’t done. After stealing a sip of Asher’s water when he wasn’t looking, slopping through half a bowl of rice and beef and again pouring another shot for everyone, he raised a toast. Hen shifted uncomfortably. Her husband turned his attention away from the table. Angela squeezed my knee, and our guides Bahn and Zee rolled their eyes. Each time Lu took a shot, he would circle the table and shake our hands. In the brief thirty minutes he shared our meal, Lu poured a total of ten shots. Fortunately, he was intoxicated enough that he didn’t notice (or perhaps care) that no one joined him in the toasts…except for me. I stayed with him for the first five or six.

We were lucky that the homestay had a shower and a Western style toilet – true luxuries in these mountains. Each of the guests took turns getting cleaned up before bed. Sleeping arrangements included the following items – a thin mat laid on the floor, a pillow, a blanket and a mosquito net. Each of us had our own mat in the attic of the house. The wind that howled and whistled between the seams of the corrugated steel roof was alarming at times. I didn’t sleep well, but the rest of my bone-weary family seemed to fare better.

THE LONGEST DAY

Pre-dawn crows echoed across the valley as roosters from every farm marked the start of another day. We pulled on our still-damp clothes from the previous day and met outside for a breakfast of pancakes, fresh bananas, honey and coffee – fuel for what would be the longest day of our travels in Asia.

We hiked four more miles from Ban Ho to Lao Chai. The trek took us through the more populous and touristy villages, and gave us an opportunity to see a chicken being prepared for lunch and a pig being cleaned (EVERY part of it) for a wedding. At Lao Chai, a van drove us back to Sa Pa where we took a quick shower and had lunch. Then we were back on the winding roads down out of the mountains to reach the Hanoi airport. Our driver had misjudged the amount of time it would take to get to the airport plus got lost during the final 30 miles, so we barely made our flight. Two hours later, we arrived in Luang Prabang in the dark of night. The lights in the airport – the entire airport – flickered on and off as we went through the Visa application and passport control process. As in Vietnam, we had to pay in American dollars. After getting our bags, the driver (Mr. Ae) and guide (Mr. Ting) delivered us to our hotel. It was 9:00p.

Luang Prabang is a small town of around 50,000 people. The short drive to the hotel was a chaotic murmuration of motorbikes and bicycles, with passengers’ faces hidden behind brightly colored surgical masks. The acrid pall that enveloped the town combined with the bright red and yellow lights illuminating the night markets were surreal.