Contrasted with the sweat and strain of Southeast Asia, we found Japan a nation of sublime balance where strife and urgency are juxtaposed against natural beauty and human aesthetics.

We arrived in the early hours, having spent the night flying from Saigon via Singapore. It was cool and the sun was burning off the last remnants of a ghostly fog that made our new world glow. Beautiful, yes, but we were bleary-eyed and grumpy, and wisely limited our communication to simple words and gestures. Quietly we boarded the Shinkansen (bullet train) from Osaka to Kyoto – the first of many trips aboard the ultra fast machines.

CHERRY BLOSSOMS

Once the imperial capital of Japan, Kyoto is known as the City of Ten Thousand Shrines. The first “shrine” we wanted to visit was our hotel, aka the Shrine of the Weary Traveler. Our temporary home was unassumingly embedded in a quiet residential area three blocks from the Kyoto Imperial Palace.

As we arrived by taxi, a squad of young women in pink dresses with matching pink caps greeted us at the door and unloaded our heavy bags without strain. They smiled and bowed and guided us into the desk, walked us over to the restaurant and ushered us up to our room. After they left, we drew the shades and crashed for 16 hours of blissful sleep.

Kyoto is famed for its cherry blossom viewing, but we were a little late, missing the peak by a couple of weeks. It’s a very important aspect of the Japanese culture and many citizens have their own cherry tree they’ve attached special significance to during their lives. In Cambodia, I sat one afternoon and watched four hours of NHK World shows, including one entitled “Ten Tales of Cherry Blossoms.” It helped prepare us for the blossom reverence we saw throughout Japan.

As we walked through the grounds of the Imperial Palace, an arbor of late-blooming trees attracted swarms of locals. They hovered along the periphery of the grove and zoomed in to inspect the cream and pink snowballs up close, then retreated to snap pictures. Grown men in business suits grinned and laughed like kids. Students in uniforms climbed under the low hanging boughs to lie in the cool grass and look up through the flowers. Couples held hands or cuddled as solicited passersby took their picture. They buzzed with excitement, bouncing along the edge of the trees and brushing the flowers on their cheeks.

FINDING HARMONY

Kyoto’s Kinkaku-ji, or “Golden Pavilion,” is one of the city’s most famous and visited shrines. The main hall is luminescent, a golden three-story pagoda that reflects brightly off the calm waters on which it is perched. The pea gravel track through the surrounding grounds leads visitors to a cul-de-sac where photographers with tripods and tourists with iPads stop to snap pictures. It was originally constructed in 1397 as a retreat for the local shogun and eventually was made into a Zen Buddhist temple. Minimalist in design, it is comely nonetheless wrapped in the thin sheet of gold leaf.

What struck us about Kinkaku-ji and the other shrines we visited in Kyoto, in fact throughout Japan, was how well man and nature complement one another. It’s certainly not without effort and a vigilant long-view perspective. So often, the boundary between humans and earth is spiritual blight; suburban malls and shanty sprawls, where the economic utility of inner space comes at the cost of outer surrounds. Trees are shorn without consideration, sod replaces indigenous wildflowers and streams flow through dark steel culverts beneath roads. But in Kyoto, symmetry is a garden that is always in bloom.

We too found a balance – deciding early that our visit wouldn’t be over-striving. Quiet streets were strolled and alleys were explored for nothing in particular. No hustling among the crowds. It was peaceful to slow and listen to the breathing of the city around us. All we wanted was to feel some connection with the rhythm of Kyoto. We did spend a long afternoon climbing the trails under the torii gates of Fushimi Inari Taisha, a Shinto shrine set among the eastern hills where the boys and I wrote haikus as we strolled:

Walking in silence/through gates of orange and black/the creek at my side.

It was rainy and cool during our tour of Kyoto, a very welcome change. Angela and Ronan visited Gion and Kiyomizu-dera, a temple carved into the steep slopes of the mountain overlooking the city. The temple is famed for its 13meter-high stage from which monks would make a wish then throw themselves off the platform. If they survived, the wish would come true.

We all visited Ryoan-ji and Daitoku-ji where we sat and ruminated on the kare-sansui, or rock garden. Borrowed umbrellas weren’t enough protection against the downpour as we rambled through the Arashiyama district and toured Tenryu-ji, our pants soaked. There we discovered a Japanese giant hornet, a horrifyingly large insect that is the stuff of nightmares. It moved slowly – wet and cold like us, waiting out the rain beneath a stone fountain. We passed through the bamboo forest in the Sagano district at the edge of Tenryu-ji, then as we made our way back to the train station the boys bought pork pastries and fried chicken from street vendors.

The food in Kyoto is incredible. We gorged on ramen and soba, sushi and Mexican. Yep. Mexican. After so many months away from California, one of our universal longings was for a solid burrito and we found one in Kyoto. LaJolla, a restaurant created by a Japanese woman who lived in Southern California for a few years, was a welcome treat.

LaJolla had recently moved from the address we’d been provided, so it was work to navigate our way there (burritos were the proverbial cheese at the end of the maze). Fortunately, we received the help of an elderly woman pushing her motorbike. She was sweet, smiling at us and staring into the ground as she searched for the English words to help. She understood us much better than she could respond. Most Japanese learn English in school, but not all have equal opportunities to practice it. She struggled a bit but we were grateful for her attempts, as we couldn’t do nearly as well in Japanese. And she certainly didn’t need to help us, but must have seen the looks on our faces when we thought we might not get a much-needed bowl of guacamole.

SHINKANSEN

More than 11 million passengers use the Shinkansen (bullet train) system in Japan each year, which accounts for more than 60% of the world’s high-speed rail users. It seems perfectly reasonable that the Japanese would use this high-quality, superbly reliable transportation system for traversing the country. Traveling from Tokyo to Osaka for example, a distance of around 500km, takes approximately 7 hours by car, 2.5 hours by Shinkansen or 1 hour by plane, but the train requires less than two minutes of boarding time and provides spacious seating.

For us, the bullet train was exciting; watching it roar through the stations and feeling it push us back in our seats as it accelerated to 200mph was a thrill.

PAPER CRANES

Sadako Sasaki was only two years old when the A-bomb devastated Hiroshima. Initially one of the lucky ones who survived the blast, she showed no signs of injury and grew into a healthy young girl until the age of nine. An illness was then revealed to be leukemia and Sadako, which means ‘innocent child,’ began a fight for her life. Believing that folding colorful paper cranes helped in her healing process, she spent the last eight months of her life folding countless graceful cranes with delicate hands. Sadly, the lingering effects of the bombs kept killing long after schools were rebuilt and normal services restored in Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The A-bomb was dropped on Hiroshima on August, 6 1945 at 8:16am; Sadako Sasaki died on October 25, 1955. It is estimated that more than 10 million cranes are offered each year at the Children’s Peace Monument.

In a world locked in conflict over religious ideologies, it is challenging – if not impossible – to believe in the concept of universal truth. Common notions of freedom or justice or family have become objectified by opponents – tolerances narrowed to highlight difference, emotions amplified to spur action against those differences. Consider Auschwitz. Wounded Knee. Srebrenica. Ground Zero. Stalingrad. Yet, standing on ground where thousands of people lost their lives due to genocide or war, accident or terrorism is a coalescent function. It reminds us of the bird-bone fragility of life and that, after differences are discarded as superficial, we are human.

Hiroshima is one of the most sacred grounds in the history of the world, and in that it is a living legacy, a paradox. Seventy years ago, this broad valley with romantic views out to the sea was wholly destroyed – its buildings flattened and burned; its people poisoned and dead. Yet today, atop that solemn foundation, it is vibrant and bustling with people pulsing through its avenues, visiting shops and restaurants as illuminated as a Saturday-night carnival. It is very much a place of living; it shows almost no scars.

NOBODY TALKS, NOTHING CHANGES

The Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum is a collection of artifacts that survived the blast. There are many physical exhibits that show technically amazing things, such as two-inch-thick rolled steel beams that were twisted into abstractions, or hundreds of apothecary jars that had been melted into a solid chuck of glass.

There’s also the pocket watch owned by Kengo Nikawa, frozen at 8:16am. It was a gift from his son and something he considered precious. He died a little more than two weeks later from grievous injuries sustained in the blast. Kengo had been riding his bike to work.

There’s the tattered and ash-streaked uniform worn by Nobuko Oshita, a 13-year-old student at the girls’ high school. After being exposed to the bomb, she fled into hiding with a classmate, where relief workers found her and returned her home to her family. Nobuko died the following day, still wearing the uniform she’d made.

And there’s the lunch box of Shigeru Orimen, a junior-high school student whose body was found nearly four days later by his mother. Shigeru had been tending the family’s garden while his father and brother were away at the front. His lunchbox contained a meal made from his first harvest – something he was so proud of yet never tasted.

This museum, like the Normandy American Cemetery and the Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe, left an indelible mark on our psyche. It is a powerfully moving place filled with stories that raise unanswerable questions. The boys were exhausted and silent as we walked from the darkened exhibit hall back into the lighted gallery that looks out across the park, the A-Bomb Dome silhouetted against the blue sky. There, along the windows, Asher found a table where local volunteers were teaching kids how to make paper cranes. He sat down with Angela and decided to make an offering of peace in honor of Sadako Sasaki.

WHITE GLOVE TREATMENT

In Vietnam, taxi drivers will often sleep in their vehicles until they are hired, or if they’re waiting for you to visit a site, they will smoke cigarettes and stare at their phones. In Japan, the drivers wear white gloves and their vehicles are pristine – clean, pleasant-smelling and shiny. Most of our drivers wore masks to reduce the exchange of germs. They also bow and smile and refuse your help with either the doors (which open automatically) or the luggage. The taxis are also very expensive and, given the countries exceptional public transportation system, mostly unneeded unless you are in a hurry to make the train, which we were for the Shinkansen from Hiroshima to Koyasan.

GRAND MASTER WHO PROPAGATED DHARMA

Kukai was an aristocrat, born in 774 in the province of Sanuki on the island of Shikoku. Famous as a calligrapher and engineer, he became an important spiritual and political advisor to the Emperor Saga and eventually won favor to create a Shingon Buddhist retreat amidst the lush mountains and towering pines south of Osaka in 819. Since its founding, Mt. Koya has grown from a single shrine to a network of more than 120 temples. This has transformed the peaceful region into a noisy and kitchy tourist village (albeit a beautiful one), where pilgrims and those interested in learning about Buddhism can live among monks for a night or two.

Our arrival in Koyasan wasn’t easy. We took the Shinkansen from Hiroshima to Osaka, a local train to Koyasan Station, then a cable train (pitched at a 45 degree angle) to the top of the mountain and finally a bus delivered us to our temple. We removed our shoes at the entrance and carried our backpacks up to our room. The simple accommodations had no TV, Wifi or running water; only mats and pillows on tatami floors.

For 24 hours, we lived as monks. We ate vegetarian food served on chabudai, or low tables, as we sat cross-legged in the silence. The next morning, we rose at 5:00am to participate in prayers – an hour-long series of rituals that included chanting and burning of incense with explanations by the one monk who spoke English.

After prayers, we walked along the roadway to Okunoin, Koyasan’s sprawling cemetery set beneath the pines on craggy ground. It is where Kukai’s mausoleum is located – a place where he is said to have settled into an eternal mediation rather than to have died. Surrounding his tomb are more than 200,000 stone stupas, some simple and others quite ornate. The paths through the forest were many, and we soon lost ourselves to the deep evergreen silence in this holiest of places.

RESTROOM BREAKS

Japanese toilets come with elaborate control panels. Seats are heated, as is the washing spritz, which can be perfumed, warmed and customized for men and women. Some of the toilets were complicated enough to require a laminated instruction sheet providing details for their use. The exceptional quality and complexity of the toilets held true for public restrooms as well as in hotels. Even the toilets at the austere monastery in Koyasan were nicer and fancier than anything we’ve seen on our journeys or at home.

HAKONE

The first thing we noticed about Lisa, our nakai for the next two days, was that she was strikingly beautiful. Exceptionally tall with olive skin, her enormous brown and amber-flecked eyes and serene smile could have put her on the cover of a magazine. Yet for us, she bowed courteously and explained in antipodal English the basics of our stay at the ryokan. Lisa, born to a Japanese mother and Kiwi father, was an apprentice frequently shadowed by an elderly woman who coached her (in Japanese) on how to be a proper nakai.

A ryokan is a traditional Japanese inn – tatami-matted rooms and sliding paper walls separate the sleeping, dining and relaxing areas. They frequently have communal baths and great common rooms or secluded outside gardens for sitting and relaxing. Upon arrival, our bags were taken from us, as were our shoes, which we left at the front door for the duration of our stay. The innkeeper in a bespoke suit stood at the head of a line of his staff, who bowed and welcomed us. A young man with shoe duty disappeared to find larger slippers for us, our first indication that this might be a ryokan more frequented by native Japanese than international tourists. We welcomed this as good news.

NAKED COMMUNION

An onsen is generically a public bath, though the term technically means hot springs. In Hakone, a volcanically active region sitting within the geo-thermal foothills of Mt. Fuji, our onsen was both public and naturally heated. It was also a completely new experience for us. We’d visited the Széchenyi baths in Budapest and several hot pools in Iceland, but both of those required swimsuits. The boys weren’t excited to bathe nude in super-heated waters with strangers. The men’s and women’s baths were segregated, so we parted ways with Angela and headed into the unknown.

We first visited the large onsen inside the main pavilion overlooking the verdant valley of bamboos and ferns. We observed the pre-bath cleaning ritual of sitting on short stools at one of a dozen stations, each of which had a full compliment of soaps and shampoos, a large wooden bucket (for pouring over our bodies) and a shower head. We were the only ones in the bath house, which eased the boys’ minds a bit. After an hour soak, we wrapped ourselves in the yukata and sauntered down the hill to the open-air, creekside onsen. Needless to say, photography is not allowed in such places, but this onsen was so private that I surreptitiously snapped a picture of the three of us as we enjoyed the soothing springs.

During our time in Hakone, we mostly stayed on site at the ryokan. It was a beautiful setting and we needed time to relax. The air was crisp and cool at night, settling down from Mt. Fuji which stood invisibly above us. We enjoyed the soft sounds of the breeze through the maples and the chiggedy-chiggedy drone of the crickets. We dined on exotic foods and played cards, laughed and soaked and had a wonderful time.

On our last day in the region we searched the nearby village for Hakone’s famous puzzle boxes and visited the gorgeous Hakone Open-Air Museum, where Asher climbed up and through the “Woods of Net,” an enormous hand-crocheted play structure designed by Toshiko Horiuchi MacAdam.

KETCHUP/BEER DIPLOMACY

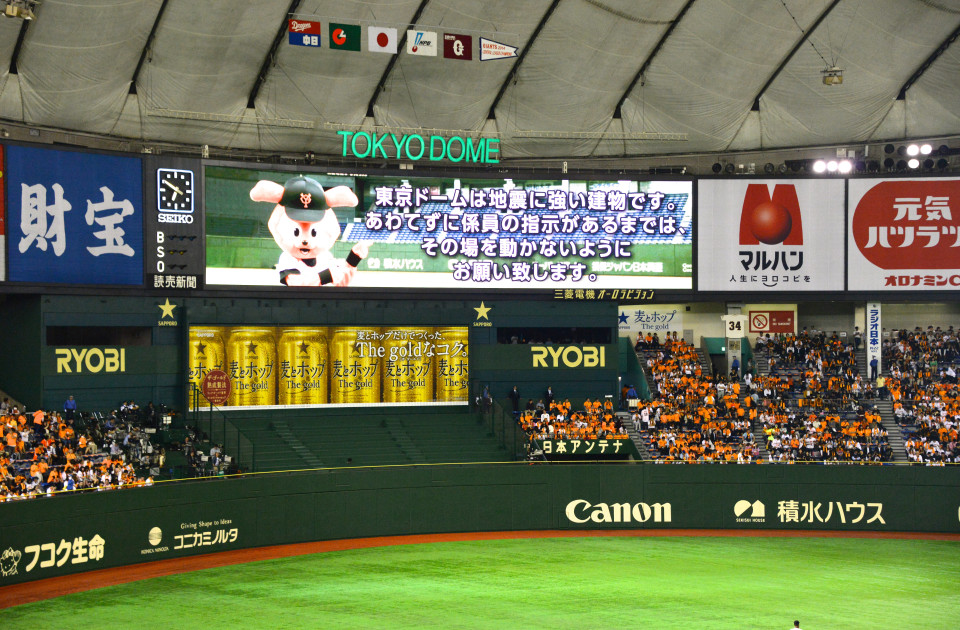

He was a nameless baseball fan seated directly in front us, clearly enjoying the game with boisterous work colleagues at the Toyko Dome. He wore that night’s promotional giveaway, a bright orange t-shirt of the local team, the Yumiuri Giants. We had four of the same shirt ourselves.

While the game of baseball in Japan is virtually the same as in the U.S., the experience was surprisingly different. Fans coordinated chants and sat quietly when their team was pitching, cheering only when outs were made or homeruns struck. The opposing team sat in a designated area in the outfield. No one barked obscenities at the umpires on questionable calls. No one taunted the other team or their fans. The Tokyo Giants’ had a cheerleader squad who danced and entertained between innings, while the beer girls climbed the aisles and served beer from backpack kegs.

Our seats were on the lower level near the Giants’ dugout, and the home team was playing the Chunichi Dragons. The logo and colors for the Giants mimicked our own San Francisco team; the Dragons curvy script and blue and white colors reminded us of the Dodgers. The visual similarities made it the ideal rivalry for us and we resisted the urge to chant, “Beat L.A.!” Stadium concessionaires offered standard fare – beer, hot dogs, French fries, popcorn and nuts – but also more exotic items such as whiskey, sushi and noodles. It was the decision to try a Japanese hot dog that introduced me to the man sitting in front of us.

Inattentively I squeezed a ketchup packet, which suddenly burst and sprayed a thin ribbon of red across the back of the nameless gentleman. He didn’t feel it, didn’t react. There ensued a brief debate between my sons and me on how to handle it. We were worried that he might not speak English and thus make it difficult to explain what had happened, that it was an accident and that I’d like to exchange his soiled t-shirt for one of ours.

I tapped him on the shoulder and tried to explain. He spoke no English. I pointed at his back and showed him the now empty ketchup packet. He didn’t understand. One of his friends leaned back and turned to his friend to explain. I offered the t-shirt exchange and to buy him a beer, but his colleague said not to worry, “he doesn’t really like the Giants anyway.” But the nameless gentleman who didn’t speak English and who had a growing red smear on his back tilted his head back, pointed at his empty cup and said, “beer.” They were all laughing as I ran to purchase the largest beer available, and the event earned my friend a new nickname among his colleagues – “Ketchup.”

THE SCRAMBLE

We had only a few hours until our flight from Tokyo to San Francisco, but wanted to visit the throbbing heart of the city – Shibuya Crossing. It looks like a square straight out of “Blade Runner,” with giant video screens and neon signs that tower over throngs of shoppers. Every few minutes, all of the traffic lights turn red and thousands of people cross the intersection from every direction. There are cafés and bars where one can sit and watch the rhythmic pulsing of machine and man.

It was midnight when we left the hotel aboard the airport shuttle. The metronomic pace and inimitable beauty of Japan was on display throughout our time there. The country was clean and orderly, dynamic and formal, and for us it was a wonderful time. We had a 10-hour flight ahead and, despite our new-found love for this country, longed to return to our own.

Mark, ALL of your journals are amazing. This will be a book someday!